My papa doesn’t invite me on holidays anymore. I’ve grown up and find it hard to make it home for the 5:30pm dinnertimes whilst working a 9-6 and have become the elusive older sibling without meaning to. Which means family holidays have become an unattainable desirable thing that I grapple towards, forgetting a long childhood of fearing them. Holidays with my mum meant lying on a beach and eating dinners out, whereas going away with my papa felt like a sort of survival course, through which I would emerge the other end tanned, toned, and slightly malnourished.

My first memory of our walking holidays is a trip to La Gomera. We stayed in a rundown motel with three small camp beds and a shower that only ran cold. Each morning, we’d wake early to catch a small local bus that only came hourly. It always had the radio on blasting outdated English pop songs, and I would insist on singing along, suddenly proud that I had some higher claim to the language. In London I never feel very English, always other in some way, but the moment I am in Europe I understand I am alarmingly so. And suddenly on this small shaky bus hurtling along the winding roadways on the mountainside, my Englishness feels a point of pride allowing me the secret knowledge of understanding the lyrics to a Justin Timberlake song.

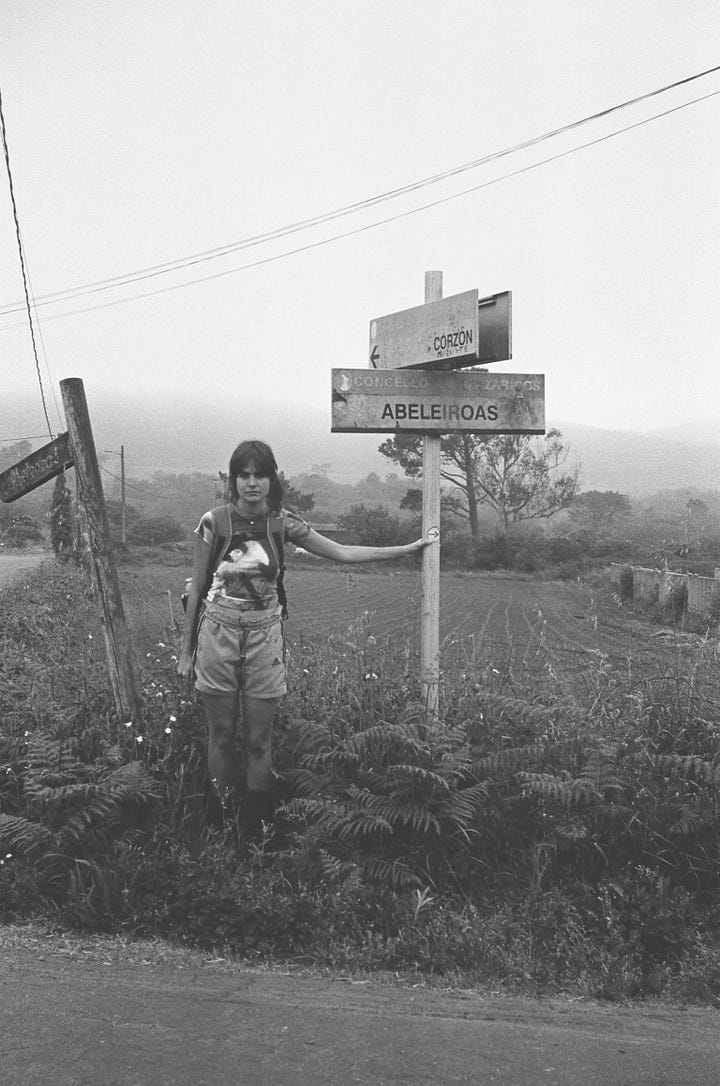

Eventually we would reach a picturesque spot, where the bus inhabitants would disembark to take pictures, and then, I would watch with betrayal as they reembarked and drove into the distance and we were left on the bare roadside.

My memory of that holiday are dry and dusty. Walking up mountains which always seemed like they had just suffered a wildfire and filled me with a sort of existential horror. Barren landscapes have always provoked a deep discomfort in me, like I am on the edge of humanity, understanding suddenly my own smallness, and a certain meaninglessness to everything. I can’t really explain it. Like doing DofE as a teenager, and crossing over an abandoned plane field, from which both directions just showed you a flatness, I understood this to be a very bad place. A place to get out of as soon possible. Is flatness evil? The opposite reaction staying on a farm in Tuscany, looking out from our point in the middle of the valley to lush green fields above and below and rolling hills, everywhere different levels. Walking anywhere requiring going up and down and up and down, the pointlessness of it somehow meaning-making. Is life just finding ways to go down and up and down and hopefully up for a long long time?

In La Gomera we never walked straight, always painfully up and up forever, and then suddenly all the way down. We would walk for 8 hours a day over tall mountains. Across the badlands, passing by prickly pears and tiny lizards and small animal skeletons and burnt out trees and would see no one. And I would think about death - too young to understand I was thinking of death.

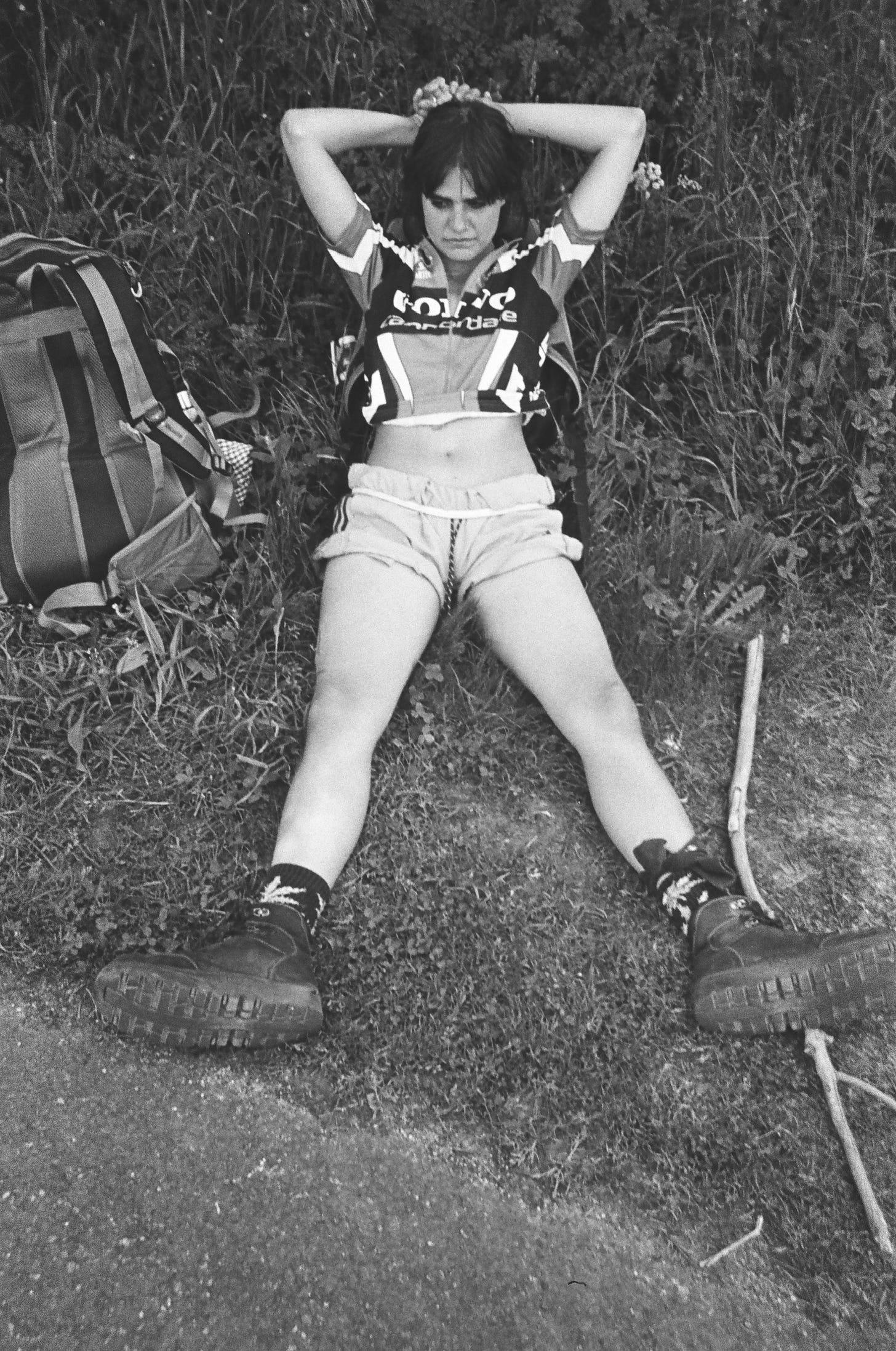

On one ascent I sat down and began crying as we were 15 minutes from the top (or that is what I was told anyway, but at this point I was distrustful, understanding these estimates as just a way to keep me going and full of lies). My brother and father insisted I had to keep going - what was the point of coming all this way not to reach the top? But I realised I didn’t care, I learnt my own lesson that day, not to do something just for the sake of it. What was the point of reaching the top anyway? the view 10m better than the one I was already seeing? a weak sense of completion?

So, they continued to the top and I stayed sat on my hard rock looking out over the dry grounds below. Seeing the spots where I had previously been - the echo of my small body that had traversed the land behind me. A sense that I was still there, the tree in the far distance that I remembered an hour before tracing my fingers across its shiny paperlike skin. The rock where I scraped my knee. Now blurry and powerless and small as a fingernail.

I could no longer hear or see my family; I was entirely alone. With a rush, I realised that there was no certainty of their return, no tangible proof, even, that there had ever been anything else in the world but me and this emptiness. London feeling impossible. I was a singular vulnerable body that had stepped out of time to this solitary existence. Maybe on that mountain top was my first understanding of the body’s shaky visibility, how easily it disappears. My own inability to understand my existence without the presence of others. And so, I spent some time in nonexistence. Until - just like that - they returned. With the warning sounds of rocks underfoot, they rounded the cliff face, and, again I existed. As if nothing had ever happened; other than my Papa’s new understanding of the truth of my vulnerability, that one day I would no longer be under his protection, the world may beat me down and I may just sit down and not get up again. With this shift between us, we began our descent. A mountain’s descent is harder than its ascent, you spend the whole time bending your knees and crouching forward, sensing gravity trying to topple you over so you must concentrate extra hard on staying vertical. Often, we would fall into silence as we went down.

Papa was an almost-Olympic athlete when he was young, most of the photos of his youth show a tanned six-packed young man in tiny Kappa briefs on a running field. I grew up hearing stories of intense regimes and how everyone would throw up at the end of training from exhaustion. Growing up roaming the streets of Torino, with lack of much parental involvement, athletics training became a second home and source of adult guidance, and I think he hoped the same for us. Wanting to teach us resilience and emotional strength through physical exertion. On Thursdays, he would come to the track after work and make me run 300m again and again, shouting motivational life lessons at me like ‘you are stronger than you think’, ‘you must always keep going even if it’s hard’, ‘you can do it you can do it’ . I like to think somewhere it stuck. That I have some improved level of resilience. Me and my brother were both enforced into athletics training from 10 years old, but where my brother excelled and started competing in 100m and 200m running competitions, I cried and complained and pretending to go on jogs, but my dad would sniff my shoes and catch my bluff. As a teen I would go out on a ‘run’ and sit on the overpass of a nearby motorway for an hour and look out at the passing cars, everything awash in grey, until it got dark, and the cars became streams of neon lights.

Which is to say on these holidays my older brother and father would pace ahead, and I would trail behind and view myself as being female and frail and very little compared to them, and it all felt very unfair. I would always lose my appetite and refusing to eat. The only food brought on these walks was bread, sliced jamon and possibly a wafer biscuit. I hated these dry cured meat and plain bread sandwiches. Dry landscape, dry food, dry mouth. It was too much.

We would always run out of water when we were still hours from the end. My throat being infiltrated by dry mud and trying to conserve saliva. And I would dream of the point when we would reach the first bar, and I would sit at the high stools, my feet dangling off the ground, and my dad would buy us all cold bottles of peach iced tea and it truly tasted like joy. I can never get back that experience of heavenly ice-cold Lipton’s going down my dry throat, sweet and smooth, as I sat down for the first time in hours, sensing my tired aching limbs, feeling I deserved this drink more than anyone else in the world. Maybe it was all worth it for that first perfect sip.

This is really really great